An extract from

The Reckoning

You thought you were a mind, but you’re a body, you thought you could have a public life, but your private life is here to sabotage you, you thought you had power so let us destroy you.

Rebecca Solnit

Prologue

Sunday 27 October 2019

‘The problem with most people,’ said Narinder, ‘is, at their heart, they’re fundamentally opposed to any sort of meaningful change, even when it would demonstrably improve their material circumstances.’

She spoke earnestly, emboldened by a combination of the alcohol in her bloodstream and a certain innate self-assuredness that one of her former schoolteachers had once remarked to another would either take her far in life or bring her to a sharp and sticky end. To date, it certainly hadn’t held her back.

Judging by their expressions, her three friends were less than convinced, though not exactly surprised to be treated to such an impassioned declaration. They were perched on tall stools, clustered around a small, circular table a convenient stone’s throw from the bar. Taken together, the low mood lighting and tasteful R&B music on the speaker system suggested a far mellower ambience than the one Narinder seemed intent on engendering.

‘So you win them round gradually,’ said Eva, her perfectly manicured fingers toying with her straw. ‘You introduce reforms bit by bit, instead of spooking the horses by trying to introduce anarcho-communism overnight.’

Narinder gave a dismissive pfff. ‘Gradualism’s a total cul-de-sac. It’s just a way for the establishment to keep us lefties in our place. And why do they keep getting away with it?’

‘I’ve a feeling you’re going to tell us,’ said Soledad.

‘Because we’re too damn nice for our own good.’

The others shared surreptitious glances. Evidently, they weren’t buying it.

‘We always end up compromising,’ Narinder went on, undeterred, ‘while they never budge an inch. They keep telling us, “What you’re asking for is too radical. Let’s meet in the middle instead.” And we go along with it like suckers, while the so-called middle shifts further and further to the right.’

‘All right then, Miss “I’ve got a PhD in rabble-rousing”.’ Camille leaned her folded arms on the sliver of space on the table that wasn’t crowded with empty and half-empty glasses. ‘What’s your solution?’

Narinder shrugged, as if the answer was obvious. ‘We’ve gotta stop playing their game. Stop trying to achieve our aims through the systems they built with the express purpose of keeping us in our place.’ She snorted. ‘What, you think the Yanks or the Irish would’ve gotten their independence if they’d just kept asking nicely?’

Camille regarded Narinder with a look of incredulity. ‘So you’re saying… what? That we ought to abandon the ballot box and take up arms instead?’

Narinder shrugged. ‘No pain, no gain.’

‘But who gets to decide when violent action is justified?’ insisted Eva, adamant that she wasn’t going to let such an incendiary remark pass unchallenged. ‘Certainly not the ones advocating for it. I reckon they might be just a teeny bit biased. You’ve got to have some sort of system that acts as a neutral arbiter – some way of laying down rules everyone respects.’

Narinder snorted. ‘You think the ethno-nationalists and neo-fascists have any respect for the rules? That’s half our problem. The other side are busy tearing up the rulebook while we cling to it out of desperation, kidding ourselves it still means anything.’ She picked up her glass and gesticulated with it animatedly, as if to reinforce her point. ‘Besides, there’s such a thing as moral justice, even if it conflicts with the law.’

‘But that’s my point. Everyone thinks their cause is morally just. So did Pinochet. So did Hitler.’

‘Well, if you have to invoke your actual Hitler, you’ve lost the argument before you’ve even started.’

Narinder fortified herself by downing the rest of her drink in a oner.

‘I’m telling you,’ she continued, setting her glass down with a thump, ‘it’s the radicals and extremists who see the world as it really is – far more clearly and accurately than the supposed moderates, most of whom are actually just fascists without the courage of their convictions. It’s your so-called fanatics who actually understand what needs to change and have a plan for achieving it. Everything else is just waffle.’

This time, judging by the eye-rolls and groans of incredulity, there could be no doubting she’d comprehensively lost her audience.

‘I think someone’s had a few too many margaritas,’ Eva muttered to Soledad.

‘Hey,’ said Narinder, ‘I can’t help it if I’m full of piss and vinegar.’

‘But mostly piss,’ said Soledad.

Eva and Camille both laughed uproariously. Even Narinder joined in somewhat sheepishly, recognising that she’d pushed her rhetoric to the point of absurdity.

‘All right, all right.’ She raised both hands in a plea for truce. ‘Maybe I am getting just a tad carried away. But I’ll tell you one thing for certain: the four of us’ll be dead from old age before the politicians and armchair experts get off their arses and lift a finger to make this world a better place.’

This earned her a rousing chorus of agreement. On this, at least, they were on the same page.

‘Well,’ said Camille, folding her hands primly in her lap, ‘at any rate, we’ve established one thing beyond a shadow of a doubt: when the revolution comes, it’ll begin in the wine bars of the West End.’

The others whooped uproariously in agreement and clinked glasses, their earlier ructions forgotten.

They spilled out into the street in the wee hours, bundled up in their winter coats, their continuing sounds of merriment carrying in the still night air till Narinder’s taxi pulled up. Following multiple rounds of full-bodied hugs and boozy kisses, accompanied by earnest pledges to get in at least one more night out before the year’s end, Narinder tumbled into the back seat, serenaded on her way by a chorus of farewells.

As the cab pulled away, Eva snapped a photo of the departing licence plate and texted it to the rest of the group. An excessive precaution, perhaps – but then, no one ever came to regret being too careful.

Less than half an hour later, Narinder let herself into the communal hallway of the converted sandstone townhouse in Shawlands where she and her flatmate lived. There, she got out her phone, opened the WhatsApp group she shared with her three friends, and tapped out a message:

Home safe and unmolested. Sweet dreams my gorgeous bitches XOXO

She headed up to the third floor and let herself into the small, cluttered flat. She locked the door behind her, then hung up her coat, kicked off her heels and once more inspected her phone. The lock screen informed her that it was 2.38 a.m. She groaned inwardly, before setting her alarm for 7.30. She had a supervision meeting at 9 a.m. sharp. Who in their right mind scheduled a meeting for nine o’clock on a Monday morning? A sadist, that’s who.

Barefoot, she sloped through to the kitchen, grabbed a bottle of mineral water from the fridge and headed through to her bedroom, necking from the open bottle. Having drunk enough to quell her raging thirst, she set it down on the nightstand and began to get ready for bed.

As she struggled with the zip at the back of her sequin top, she failed to notice the lithe figure dressed from head to foot in black slipping out from behind the open door and making his silent way across the floor towards her.

‘Fucksake,’ she muttered, her fingers once again failing to make purchase on the pesky zip.

Behind her, a floorboard creaked.

Spinning around, she found herself staring into two piercing eyes, drilling into her through the narrow slit of a balaclava. She only managed to let out a brief, frightened squeak before a hand clamped over her mouth.

The figure flung her backwards onto the bed, straddling her before she had time to recover. With his weight bearing down on her midriff, he continued to cover her mouth, the force of his hand pressing the inside of her upper lip into her teeth. Her nostrils flared. She tasted the metallic tang of blood. He leaned in close, their noses almost touching, his eyes glinting in the half-light from the bedside lamp.

A powerless scream rose up from her diaphragm and escaped through her nose in a near-silent exhalation of air.

Seconds later, his fist connected with the side of her head, and her vision exploded in a kaleidoscope of stars.

1

Monday 28 October

‘This is Farah Hadid. Unfortunately, I’m unavailable right now. Please leave a message and I’ll respond when I am able.’

Anna, standing in the corridor with her phone clamped to her ear, waited for the sharp beep before speaking.

‘Farah, it’s me again, still wondering where you’ve got to.’

She glanced over her shoulder as the door to the meeting room opened and her boss, Fraser Taggart, leaned out, shooting her a questioning look. She nodded an acknowledgement, raising an index finger to signify ‘one minute’.

‘Look,’ she went on, as Fraser ducked back inside, ‘they’re ready to get started. I’m going to have to go in. If you get this… I don’t know, just get here as soon as you can. I’ll stall them for as long as possible. I…’ She hesitated. ‘I hope everything’s OK.’

She ended the call, took a deep breath, steeling herself, then headed in to join the others.

In total, there were fifteen women and men already seated at the long conference table that took up the bulk of the small, airless room – all senior figures within the School of Social and Political Sciences. Fraser had already assumed his position at the head of the table. Lanky, sandy-haired and dressed in an overly tight shirt with rolled-up sleeves, he was forty-five but seemingly determined to pass for at least a decade younger. On a good day, he was just about able to pull it off. He biked everywhere and was frequently to be seen power-walking along the corridor to his office first thing in the morning, clad from head to toe in Lycra. To Anna, he gave off the whiff of someone who was trying overly hard to impress someone – though who that might be was anyone’s guess.

In stark contrast, the occupant of the seat nearest the door was making no effort to project an air of anything other than disdain for the whole enterprise. Sporting a thick shock of black, oily hair and dressed in a sports jacket and an unironed, open-neck shirt that struggled to restrain his bulging belly, Robert Leopold, the recently appointed Professor of Social Anthropology, sat with one short, stubby leg folded over the other, scrolling on his phone with a pudgy index finger. He briefly glanced up at Anna before returning his attention to the glowing screen.

‘Good of you to join us, Anna,’ said Fraser. ‘Everything all right?’

It was possible he was being sarcastic, but Anna couldn’t detect any hint of it in either his voice or his expression of mild curiosity.

She nodded tightly. ‘All good.’

There was, she noticed, an empty chair next to Leopold – in fact, the only remaining one at the table. She glanced at Fraser, politely waiting for her to take a seat, and for a brief moment came very close to doing so. Then, as Leopold absentmindedly tucked his finger behind his ear and began to scratch, her resolve strengthened.

Pointedly ignoring the empty seat, she instead crossed to the other side of the room and lifted a chair from the pile of spares stacked in the corner. An awkward silence ensued, punctuated by the occasional cough, as two of Anna’s colleagues shifted sideways to make room for her. If Leopold felt in any way snubbed, he gave no sign, continuing to scroll contentedly while Anna slid into her seat and shrugged off her coat.

‘Sorry,’ she muttered, not sure who she was actually apologising to – Fraser, the two colleagues she’d displaced, or the room in general.

Fraser cleared his throat. ‘Right. Well, let’s make some progress, shall we? First item on the agenda: the upcoming industrial action by the university’s teaching associates. Obviously, minimising disruption as much as possible is paramount, so I trust you’re all putting contingency plans in place to ensure the delivery of teaching is unaffected.’

‘Do we have any feel for what proportion of the TAs will be taking part?’ asked Craig Eckhart, course director of the Economic and Social History MA.

‘The vote in favour was sixty-eight percent,’ replied Fraser, ‘and I imagine we should be anticipating a participation rate closer to one hundred. The idea of a strike may not be a universally popular one, but that doesn’t mean those who voted “No” won’t support it now that a democratic decision has been reached. The important thing is that, as far as possible, we maintain continuity of delivery…’

And on he continued to drone, a past master in the art of talking a great deal while saying very little. These meetings, held at 10 a.m. every Monday, had been his brainwave, initiated shortly after he assumed the vaunted position of Head of School. Intended to foster greater communication and cooperation between the different disciplines that had been unceremoniously folded into the umbrella of Social and Political Sciences, in reality they simply succeeded in sucking up valuable time that would have been better devoted to more productive matters, such as tackling the reams of additional admin they all seemed to have accrued ever since the ‘Great Restructuring’.

As Fraser continued to pontificate, seemingly inexhaustible in his drive to find new ways to reiterate the same stultifyingly obvious talking points, Anna chanced a glance in Leopold’s direction. He continued to pay more attention to his phone than to Fraser, occasionally pausing from scrolling to tap out a message, his thick fingers moving with surprising dexterity. She wondered that he dared be so blatant about his disinterest – but then, past experience had taught her that he was capable of getting away with just about everything short of murder.

‘…and hope for a speedy resolution that satisfies both sides in this dispute,’ concluded Fraser, having, it seemed, finally run out of banalities.

‘It seems to me,’ declared Leopold, without looking up, ‘that someone should consider calling their bluff.’

And now, all of a sudden, everyone was looking at him. He’d always, to Anna’s mind, had an infuriating ability to effortlessly command attention without so much as lifting a pinkie – of which she was more than slightly envious.

‘Call whose bluff?’ said Laura Pickering, the softly spoken Reader in Public Policy.

‘The TAs,’ said Leopold, as if it was obvious.

Everyone waited for him to elaborate.

‘The university,’ he continued in his languid, RP-inflected drawl, ‘should refuse to give them any quarter. It’s not as if they’re irreplaceable.’ He shrugged serenely. ‘If they were at all concerned about providing their students with a decent standard of education, they’d soon put down their placards and get back to work.’

‘So you think the university should blackmail them by appealing to their better nature?’ said Anna icily, even as the voice at the back of her head screamed at her not to take the bait.

Leopold chuckled softly. He put down his phone and looked directly at Anna for the first time. ‘I think,’ he said, ‘that the university should use whatever means are at its disposal to ensure it isn’t held to ransom by a gaggle of far-left malcontents who don’t know how good they’ve got it. It’s time they learned there’s a price to irresponsible agitation.’

‘And what precisely about their “agitation” is irresponsible?’

An awkward silence ensued. Everyone, it seemed, was waiting to see how this would play out. At the head of the table, Fraser shifted uncomfortably but made no move to intervene.

Leopold treated Anna to a long, hard look – less one of contempt than of weary forbearance. ‘The average salary for a full-time TA is – what? £26,000 a year? That might sound like chickenfeed to the people in this room, but tell some impoverished labourer toiling in a field in Somalia that a bunch of pampered academics in Northern Europe think earning above the national median wage constitutes unacceptable exploitation and prepare to watch their brains spontaneously combust. Come to that, tell it to the average refuse collector or supermarket worker right here in bonnie Glasgow.’

‘I think—’ Laura began.

‘That is a fatuous argument,’ snapped Anna, her voice cutting off Laura’s tentative interjection.

She knew she shouldn’t get involved in this exchange. Knew, too, that hers was precisely the response Leopold had been hoping to provoke – if not from her then from one of their other colleagues, outraged by his willingness to say the unsayable; his blatant disregard for the mores of the company in which he found himself. But she couldn’t help herself. If no one stands up to him, she thought, he’ll think he can browbeat us into accepting his way of thinking on this and every other subject under the sun.

‘In fact,’ she went on, as Leopold folded his arms and tilted his head sideways, regarding her with a look of wry amusement that she knew was deliberately designed to goad her, ‘it’s not even an argument. It’s whataboutery. It’s a ploy to shut down any form of rational discussion. It basically says no one has a right to object to their circumstances, ever, because someone, somewhere, has it worse. You might as well say, “You can’t complain about having been assaulted as long as other people are still being murdered.”’

Leopold gave a barely perceptible smirk but made no attempt to interrupt. The more rational part of Anna’s mind knew he was leaving her enough rope to hang herself. But, at that moment, the part that was spoiling for a full-blown brawl simply didn’t care.

‘It is possible to care about more than one thing at a time,’ she said, practically spitting the words out in her disdain. ‘Just because something doesn’t happen to be as bad as the worst thing you can possibly imagine doesn’t mean we shouldn’t still try to do something about it.’

And it’s not just about the pay, she thought. The TAs’ grievances were wide-ranging and varied, encompassing everything from an increasingly unrealistic workload to the fact that most of them were on term-time-only contracts, renewed on a yearly basis, to the chronic lack of opportunities to contribute to research or get onto the lecturer scale. The current dispute had been simmering for a long time, and she had nothing but sympathy for them and their cause.

But she felt she’d given him more than enough to chew over. She fell silent, quietly fuming – partly at him, and partly at herself for having allowed herself to get so riled up. Leopold said nothing, but his almost imperceptible eyebrow-raise served as an acknowledgement that her message had been received, if not accepted. He seemed almost impressed.

Fraser cleared his throat again, a wincing smile contorting his features. ‘Ahem! Far be it from me to stymie a spirited airing of views, but might I suggest that this isn’t, perhaps, the optimal venue for a debate on the rights and wrongs of industrial action? Provided everyone’s amenable, I’d like to make a little progress, if I may…?’

Anna muttered something that fell just short of actually being identifiable as an apology. Leopold shrugged amiably, as if the matter was neither here nor there to him.

Fraser beamed. ‘Excellent. In that case, I suggest we park this matter for now and move to the next item on the agenda.’ He paused to consult his notes. ‘Anna, I promised we’d find time to hear your proposal for…’ – he read from the page – ‘…“a qualitative study of the gendered outcomes for victims of crime in the West of Scotland”. Well, I’m sure we’re all looking forward to hearing what you have to say. The floor’s yours.’

All eyes in the room were now on Anna. Something shifted in the pit of her stomach. She felt her cheeks flushing.

‘Well…’ She cleared her throat awkwardly. ‘That is to say… I’m afraid there’s a slight hitch.’

‘Hitch?’ Fraser appeared confused.

‘Dr Hadid took the notes home with her at the weekend to prepare the slides for the presentation and… unfortunately, she appears to be indisposed.’

‘Indisposed?’ Leopold sounded incredulous. ‘You mean she hasn’t shown up?’ He gave a gleeful smirk, playing to the gallery. ‘Perhaps she’s decided to go on strike ahead of schedule.’

No one laughed.

‘I’m sure Dr Hadid has an entirely valid reason for her absence,’ said Anna stiffly.

‘And therein lies the danger in palming your responsibilities off on your skivvies. They invariably let you down at the most inopportune moments.’

With a monumental effort, Anna succeeded in ignoring this jibe. ‘I can do the pitch from memory,’ she told Fraser, failing to keep the faint ring of desperation from her voice. ‘But without the slides or access to our notes…’

‘No, no.’ Fraser shook his head. ‘It’s unreasonable to expect you to recite the entire thing without a crib sheet. We’ll park this for now, I think, and reschedule somewhere down the line.’ He looked around at his assembled colleagues, his expression infuriatingly jovial. ‘Well, it seems we have an opening in our itinerary. Anyone have any pressing business they’d like to discuss?’

Leopold, who’d resumed scrolling on his phone, glanced up. ‘Actually, I’d like to float a proposition I’ve been mulling over for a while.’

Fraser shrugged. ‘Does anyone have any objections?’

No one did, though Anna was sorely tempted.

Fraser gestured to Leopold. ‘Floor’s all yours, Robert.’

The others watched as, with the air of someone with all the time in the world, Leopold slid his phone into the inside pocket of his jacket and got to his feet.

‘Ladies and gentlemen,’ he announced, in his rich, sonorous baritone, ‘it strikes me that there is a significant gap in our curriculum. Namely, the conspicuous absence of a Men’s Studies course.’

Anna, who’d taken the opportunity to get out her own phone to check for missed calls from Farah, fumbled and dropped it. It hit the table with a thud, causing everyone to look in her direction.

‘At the risk of sounding presumptuous,’ said Leopold, with a note of amusement, ‘I’m going to assume that wasn’t an attempt by Professor Scavolini to signal her enthusiasm.’

‘Not in so many words, no,’ said Anna, her tone decidedly chilly.

‘Then perhaps, before I lay out my arguments in favour of a Men’s Studies programme, you might care to explain your objections.’

‘Are you sure we have time for them all?’

It was her attempt at a joke, but she saw, from the strained expressions of her colleagues, that no one had taken it in that spirit. On the contrary, the overriding mood in the room seemed to be one of quiet dread, as they all braced for a showdown to which they’d prefer not to have to bear witness.

Leopold gestured to her, a picture of magnanimity. ‘Please.’

She hadn’t expected to be put on the spot like this. She was even less prepared for this than she had been for the now aborted research proposal, and she felt the heat of mortification spreading throughout her entire body.

‘Well, I mean,’ she began, desperately hoping it wasn’t obvious to all and sundry just how unbelievably flustered she was, ‘for a start, it would put a serious strain on severely limited resources. Surely I don’t need to remind you that we already have a Gender Studies course?’

‘One which singularly fails to acknowledge the unique disadvantages men face in today’s society.’

‘Disadvantages? You mean like not knowing what to do with all the power they hold?’

‘I mean disadvantages such as the long-term psychological effects of a generation of boys being taught that they’re guilty of original sin purely by virtue of having been born male in an increasingly gynocentric world.’

‘You actually think that? You think the world is built to favour women? That’s your genuine belief?’

She already knew it was, but she wanted to hear him state it unequivocally. To actively own it. But, rather than oblige her, he merely smiled at her placidly, as if the two of them were both in possession of some intimate knowledge to which the others weren’t party.

She looked around, appealing to the gallery. ‘Can someone explain to me why it is that those in positions of power always imagine themselves to be the victims, despite all evidence to the contrary?’

But before anyone had the opportunity to respond, Fraser was on his feet, hands raised placatingly. ‘All right, all right. I’m not sure this is the most appropriate venue for a philosophical debate on the nature of systemic oppression.’

‘Quite right.’ Leopold dipped his head obsequiously. ‘It was naïve of me to attempt to advance a proposition I knew would prove contentious for certain colleagues without expecting a certain amount of pushback. I’ll submit my plan in writing through the usual channels, where it can be subjected to the usual levels of rigorous scrutiny.’ He settled in his chair once more.

‘Excellent.’ Fraser smiled, relief practically radiating from him. Returning to his seat, he consulted his notes again. ‘In that case, moving on to the next item on the agenda…’

The meeting adjourned shortly after eleven, having – as per usual – accomplished the square root of nothing. The moment Fraser called time, there was an immediate rush towards the door, as colleagues gathered their things and beat a hasty retreat, relieved to have completed their penance for another week.

Among the last to leave, Anna was on her feet and in the process of zipping up her bag when she sensed a presence by her side. She knew, even before she turned to face him, that it was Leopold.

‘I enjoyed our little sparring match there,’ he said, flashing a grin that showed off twin rows of veneers. ‘A shame it was cut prematurely short.’

‘I’m glad,’ said Anna, not returning the smile.

‘Yes.’ Leopold chuckled softly, then glanced around, as if what he was about to say was unfit for modest ears. ‘You know, if you ever fancy picking up from where we left off, there’s an open invitation to come onto my podcast to debate the matter in greater depth. I’m sure my listeners would welcome such an exchange.’

Anna laughed dryly. ‘I don’t think so.’ She shouldered her bag and turned to go.

‘Why is that, out of curiosity?’ Leopold’s tone was one of bemusement, tinged with what sounded almost like regret.

She turned to face him again. ‘Because I know how these “debates” usually go. You invite someone on with an opposing viewpoint, then proceed to caricature them and talk over them…’ She shook her head defiantly. ‘No thank you.’

‘Well, if you’re worried your views won’t stand up to scrutiny…’

It was all Anna could do to stop herself from rolling her eyes in contempt. ‘Please. If you think goading me is going to get you anywhere—’

‘Perish the thought! I’m merely suggesting that someone who’s secure in her opinions – as you most assuredly are – has nothing to fear from a rigorous exchange of ideas.’

‘Except it won’t be an exchange, will it?’ said Anna, sticking her chin forward to accentuate her point. ‘It’ll be the usual circus, where your interviewees don’t get a word in edgeways, and anything they do manage to say gets edited and clipped out of context.’

Leopold shook his head softly. ‘You don’t like me very much, do you?’ He sounded more amused than hurt.

‘I don’t like what you stand for,’ said Anna, which was also true.

‘Regardless, I see no reason why we can’t explore our differences of opinion through civil conversation.’

Anna straightened her spine, standing up to her full height as she met Leopold’s gaze. He wasn’t an especially tall man, but at five foot two, even people of average height towered over her, and the effect was amplified significantly if they stood uncomfortably close to her, as he was.

‘Well, that’s the difference between you and me, isn’t it?’ she said coolly. ‘You’ve got nothing to lose. But, for some of us, your ideas are dangerous provocations masquerading as innocent questions, and I’ll be damned if I’m going to lend them credibility by “debating” them with you.’ She shook her head. ‘Find yourself another patsy, Professor Leopold. I’m not interested.’

With that, she turned and strode out.

Anna wound her way through the network of dimly lit, linoleum-floored corridors inside the Hutcheson Building, which, ever since the Great Restructuring, had been home to her and the other refugees from the former Department of Law and Social Sciences. But, of course, there were no longer any departments, only semi-autonomous ‘subject areas’, each falling under the broad umbrella of one of the university’s twenty Schools, the groupings of which often seemed completely arbitrary, as if those calling the shots had had their hearts set on having exactly twenty, then shoehorned every subject into one of them, regardless of how unnatural a fit it proved.

For Anna, the building – a stark, brutalist monstrosity from the 1960s – served as an apt metaphor for the changing fortunes of her former department. Once housed in the grandeur of the university’s historic main building, it now felt as if she and her colleagues had been put out to pasture – exiled to a concrete high-rise on the north-western outskirts of the campus that bore more than a passing resemblance to the social housing commonly found in the former Eastern Bloc.

She wondered if that made her an insufferable snob. Someone had to be based out here, and she and her colleagues could hardly profess to hold a greater claim to their former, considerably more ostentatious lodgings than any other department… sorry, School. Still, the optics were difficult to ignore – to say nothing of the myriad inconveniences that accompanied the move, including a pronounced lack of office space and a heating system that was perpetually malfunctioning, meaning the place was invariably either unbearably hot or cold enough to freeze the very blood in your veins.

As she turned onto the corridor leading to her own cramped office, she fished out her phone and rang Farah’s number again. She wasn’t really expecting a response, and was therefore unprepared for the click, followed by the husky voice of her star TA and de facto second-in-command.

‘Hello? Anna?’

‘Farah? Are you OK?’ Anna came to a halt, pressing herself against the wall to make room for a couple of colleagues as they passed her in the narrow walkway. ‘I’ve been trying to get you for nearly two hours. The meeting—’

‘The presentation! Oh, putain de merde…’

‘What’s wrong? Where are you?’

‘One moment.’

There was a burst of incomprehensible speech on what sounded like a loudspeaker at the other end of the line, which, after a moment, became more muffled as Farah presumably covered the mouthpiece. Anna heard footsteps, followed by the voice on the speaker growing more distant. When Farah spoke again, there was a tremor in her voice which Anna hadn’t noticed before.

‘Anna, I’m so sorry. I completely forgot. I’m at the hospital. It’s… Oh God…’

As, bit by halting bit, she explained the situation, Anna felt the muscles in her jaw growing increasingly tight.

2

Anna hurried into the crowded reception area of the Accident & Emergency department at the imaginatively named Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, eyes skimming over the various signs with their directions to different departments. The bold, white text; the harsh, fluorescent lighting; the tumult of voices – it all amounted to sensory overload, multiple stimuli competing for her attention.

As she continued to cast around, the door at the end the corridor opened and a woman in her mid-twenties emerged, nose buried in her phone. With her short, dark curls and round, wire rim glasses, plus her ubiquitous black polo neck sweater and high-waisted slacks, Farah Hadid had an unassuming quality, but her distinctive fashion sense nonetheless made her easy to spot in a crowd. Looking up from her phone, she noticed Anna and greeted her with a distracted half-wave. Quickening her pace, Anna hurried towards her.

They met in the middle of the corridor, Anna instinctively offering up her cheek for the French-style kiss that was Farah’s default method of greeting. The resulting double-cheeked peck had more than an air of going through the motions about it, Farah’s mind clearly on other matters.

‘They took her upstairs to X-ray her face,’ Farah explained, once they’d dispensed with the formalities. ‘Oh, Anna, it’s so horrible. I spent the night with Émile and only went back to the flat in the morning to pick up some essays I’d been marking…’ Her hand hovered in front of her nose in anticipation of tears. ‘And when I got there she was just…’

That was as far as she got. Covering her mouth with her hand, she began to sob. Anna automatically folded her into her arms. She continued to hold Farah until her sobs subsided, before releasing her.

Straightening up, Farah gave a rueful grimace. ‘Look at me, behaving as if it was me it happened to.’

Anna shook her head, dismissing this as an irrelevance. She looked Farah up and down.

‘You going to be OK?’ she said gently.

Farah nodded tightly, eyes still glistening.

Anna led her over to a relatively quiet corner next to a vending machine sporting an ‘OUT OF ORDER’ notice.

‘You feel up to talking about it?’ she asked, as Farah, her glasses in one hand, dabbed a tissue at her eyes with the other.

‘I think so.’

‘What exactly happened?’

But before Farah could respond, they heard heavy footsteps striding towards them. Anna turned to see a large, red-faced man in a Celtic T-shirt heading their way. He came to a halt facing them and ran a hand through his hair, the agitation coming off him in waves.

‘Can you believe this fucking place?’ he asked, of no one in particular. ‘Gotta walk half a mile just to find a fucking toilet.’

Farah turned to Anna. ‘You know Callum? Narinder’s boyfriend?’

Anna nodded distantly. She knew Callum to look at, but would hardly describe them as acquaintances, let alone friends. Privately, she’d always viewed him and Narinder as the most mismatched couple she’d ever met. She couldn’t think of a single thing they had in common. She recognised that this was hardly the time and place for such thoughts, and yet she found it impossible to shake the feeling that Callum’s presence was unlikely to have a positive impact on the situation.

‘She not back yet?’ Callum directed this particular question at Farah. ‘Fuck they doing with her?’

‘I’m sure you’d prefer them to be thorough,’ said Anna levelly.

‘Dunno what the fuck they’re playing at, more like. Fucking doctors, think they know everything.’

He began to pace back and forth, swinging his arms like a pair of thick, meaty flails. Anna and Farah both watched him warily.

After a few seconds, he stopped abruptly and swung round to face them. ‘D’yous know they haven’t even let me see her?’

‘They’ll let us all see her as soon as she gets back from X-ray,’ said Farah soothingly.

‘And when the fuck’s that gonna be, huh? Doesnae take a half a fucking hour to take some pictures.’

‘Perhaps you’d like to get something to eat,’ Anna suggested, ‘or something to drink?’ She gestured to the vending machine, then remembered it was out of order. ‘Something to take your mind off it while you wait.’

'I don’t want something to fucking eat!’ Callum bellowed.

He slammed the machine with his fist, causing both Anna and Farah to flinch involuntarily. Anna took a precautionary step backwards. She was fairly sure he didn’t pose a threat to them, but all the same, it was obvious he was in an unpredictable frame of mind, and hardly predisposed towards behaving rationally.

‘All right, all right.’ With what was clearly considerable effort, Callum succeeded in moderating his tone. ‘I’m sorry, yeah? It’s just…’ He waved his hand helplessly. ‘This fucking place, yeah?’

Anna smiled and nodded sympathetically, though she drew the line at hugging him.

At that moment, she once again heard the sound of approaching footsteps. As one, they turned to see a woman in her early thirties approaching. She wore green scrubs and had dark bags under her eyes that bore more than a passing resemblance to bruises.

‘Doctor,’ said Farah. They’d evidently met already. ‘How is she?’

The woman, whose name badge identified her as Martha Keller, ran a hand through her lank hair. ‘Narinder’s doing OK, on balance. She has various fractures to her cheekbones and upper jaw, and we’re a bit concerned about the reduced vision in her right eye, but we’ll continue to monitor that over the next twenty-four hours to see if it improves.’ She lowered her voice. ‘There’s also the matter of the, um, intimate injuries she suffered. There was some tearing, as well as a small amount of internal bleeding.’

Anna and Farah glanced at one another. Both of them implicitly understood what they were being told.

‘On a more positive note, there doesn’t appear to be any bleeding on the brain,’ said the doctor, her voice returning to its normal volume. ‘I don’t, for a second, wish to downplay the severity of the ordeal she experienced, but, all things considered, things could have been considerably worse.’ She gave them a tight, but encouraging, smile.

Callum, who gave the impression of not having taken any of this in, nodded impatiently. ‘Right. So when can I see her?’

Dr Keller turned to him. ‘You’ll be Callum, then? She’s been asking after you. Saying, “Is Callum here yet?” every five minutes.’ She smiled. ‘I can take you through to her now if you like. This way.’

She led them through two sets of double doors to the main treatment area, then past a long row of cubicles until they came to one with its curtains closed. Gesturing for them to wait, she opened the curtain a crack and poked her head in.

‘Narinder, got some people here to see you,’ she said brightly.

She withdrew her head and pulled back the curtain to reveal Narinder, sitting upright on a trolley in a hospital gown. Her face was awash with livid bruises, both eyes swollen almost completely shut. She blinked painfully, clearly struggling to see.

‘Rindy?’ said Callum. The word came out as barely a whisper.

‘Callum?’ said Narinder. ‘Is that you?’

‘Jesus Christ,’ Callum murmured.

Dr Keller shot a warning look in his direction. ‘Mr Finnie…’

‘What the fuck did they do to her?’ he bellowed, somewhere between anger and disbelief.

‘Cal?’ Narinder’s voice was a frightened whimper.

Dr Keller glared daggers at Callum. ‘What’s the matter with you?’ she hissed.

‘What’s the matter with me?’ Callum stared at her in disbelief. He gesticulated towards Narinder with his entire arm. ‘LOOK AT THE FUCKING STATE OF HER!’

This was too much for Narinder. She began to cry, her hands hovering in front of her swollen face, unable to bury it in them.

‘Mister Finnie!’ exclaimed Dr Keller, unable to hide her fury. Placing herself in front of Narinder like a human shield, she brought her face close to Callum’s. ‘You’re of no use to anyone in this state. If you can’t keep your emotions in check, I’m going to have to ask you to leave.’

For a moment, Callum just stared at her, as if he couldn’t believe what he was hearing. Then his expression hardened. His fists tightened.

‘I’m gonnae kill ’em,’ he muttered. ‘I’m gonnae kill those fucking bastards. They’re not gonnae get away with this.’ He raised his voice, directing his words at no one in particular. ‘Y’hear me? I’m gonnae sort this!’

With that, he turned on his heel and stormed out, the cubicle curtains billowing behind him.

‘Cal!’ Narinder wailed, tears streaming down her cheeks.

But it was no use. Callum continued down the corridor, slammed through the double doors and was lost from view.

As Narinder sobbed uncontrollably, Farah snapped into action. Brushing past Dr Keller, she hurried into the cubicle and enveloped Narinder in her arms, whispering soft reassurances. Anna and Dr Keller remained side by side, watching them – both, Anna sensed, feeling somewhat surplus to requirements.

Slowly, Narinder’s sobs subsided. She lifted her head from Farah’s shoulder, her puckered eyelids blinking in confusion as her gaze fell on Anna.

‘Anna.’ Her tone was one of surprise. ‘You came.’

‘Yes,’ agreed Anna, somewhat helplessly. She fancied now wasn’t the time to clarify that she’d come primarily for Farah’s sake.

Narinder gestured to her face. ‘I apologise for the state of this old thing,’ she said, halfheartedly attempting to inject some levity. ‘If I’d known I’d be receiving visitors, I’d’ve put on my war paint.’

Anna smiled dutifully. ‘That’s all right.’

As Farah remained by Narinder’s side, an arm wrapped protectively around her shoulders, Dr Keller drew Anna to one side and addressed her in a low voice.

‘We’ll be moving Narinder upstairs as soon as a bed’s available. She’ll be with us for at least twenty-four hours, so she’ll need some things from home – pyjamas, toiletries and whatnot. Is that something you can arrange?’

‘Um…’ Farah relinquished her hold on Narinder and took a step forward. ‘It would make more sense if I went, perhaps? I know what to look for, and…’ She shrugged. ‘Well, I expect the police will more likely let me in.’

Anna nodded. Farah’s proposal made a great deal of sense… though she sensed what was coming next.

‘Though I don’t like the thought of leaving her on her own,’ Farah admitted, nodding surreptitiously in Narinder’s direction.

‘In that case,’ said Anna, ‘you go and I’ll stay.’

Farah looked at her, relief vying with uncertainty. ‘You’re sure?’

In truth, Anna wasn’t sure – not really. She was acutely aware that she’d run out of work on what was invariably the busiest day of the week, leaving behind a mountain of emails that had come in over the weekend, to say nothing of the teaching commitments she had to prepare for. But she could hardly say any of this – not when weighed against what Narinder was going through.

‘Of course,’ she said firmly. ‘Go. The sooner you’re out of here, the sooner you’ll be back.’ She fished her car keys out of her bag. ‘Here. Take the Skoda. It’s in the short stay car park.’

Farah accepted the keys with a smile of thanks, then turned to Narinder and, in a soft voice, explained where she was going. Narinder nodded stoically. For now, at any rate, she was succeeding in keeping the tears at bay. Farah leaned over to give her hand a brief squeeze, then headed off, flashing Anna a last look of gratitude as she went.

Dr Keller jerked a thumb over her shoulder. ‘I’ll just go and see how that bed’s coming along.’ Then she too vacated the cubicle, leaving Anna and Narinder alone together.

An awkward silence unfolded. Anna had met Narinder on roughly half a dozen previous occasions, but, all told, she knew next to nothing about her, other than that she was Farah’s flatmate and was studying for a Masters in one of the social science fields. Until today, they’d never had cause to be alone together for more than a few minutes, and Anna now found herself at a loss for words. She wasn’t great at making small talk at the best of times, and the current situation was about as far from normal as it was possible to get.

‘So tell me,’ Narinder broke the silence, ‘do I really look as bad as all that?’ She managed a small smile. ‘You can be honest with me.’

Anna looked at her helplessly, not knowing what to say.

Narinder laughed humourlessly. ‘I knew it. Well, least I’ve got my winning personality to fall back on, huh?’

Anna smiled out of obligation.

Narinder sighed, folding her hands in her lap. ‘Sorry about Cal. His heart’s in the right place, but he’s never been good at dealing with stress.’

‘I’m sure he’ll be back once he’s calmed down a bit.’

‘I just hope he doesn’t do something stupid.’

‘It’ll be fine,’ said Anna, without much confidence.

The curtain opened a crack and a young, gawky-looking nurse with thick glasses poked her head in. ‘Hi, Narinder,’ she said, with a bright smile. ‘How’re you feeling? Um, there’s a couple of police officers here to see you if you’re up to it.’

Narinder looked confused. ‘I already gave a statement to the police.’

‘Oh, right.’ The nurse was evidently thrown by this. ‘Well, I, um, think these ones are specialists or something? One’s a Detective Chief Inspector,’ she added, as if the very words were supposed to inspire awe.

Narinder shrugged wearily, as if she didn’t care either way. ‘All right. Send ’em in.’

The nurse pulled back the curtain and stepped aside as a woman and man in plain clothes entered.

The woman, who looked to be barely in her twenties, had a slight, androgynous build and was clearly aiming for ‘Alternative’ with a capital ‘A’: bleached fohawk hair; denim jacket; black skinny jeans, ripped at the knees; Converse shoes.

The man was her polar opposite in every respect. Around forty years old, he was tall, clean-cut and classically handsome – a Greco-Roman statue in a fitted suit.

‘Hello, Narinder,’ he said, giving her a friendly nod. ‘Sorry to hear you’ve been in the wars.’

He turned to Anna, who, since the moment he’d walked in, had been staring at him with a mixture of horror, disbelief and no small amount of righteous outrage. He dipped his head in acknowledgement, a small smile on his flawless lips.

‘Hello, Anna,’ said Detective Chief Inspector Paul Vasilico.

To be continued...

Buy Now

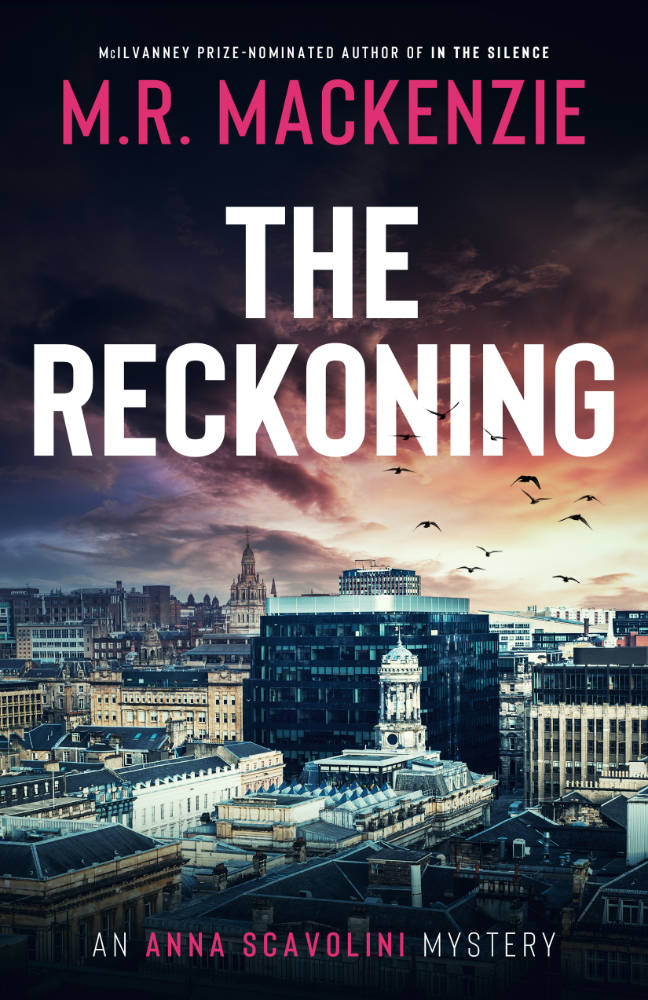

The Reckoning, the gripping fifth instalment in the Anna Scavolini mysteries series, is now available in ebook and paperback.

Kindle Paperback Signed PBK