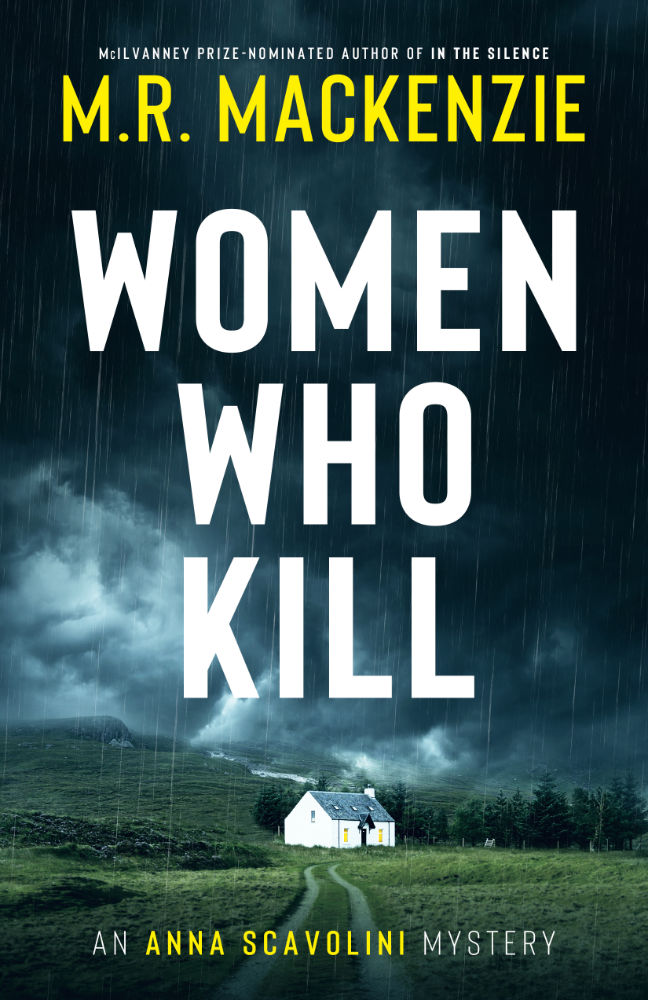

An extract from

Women Who Kill

Prologue

Wednesday 10 April 2002

‘Guilty.’

The word rings out like a tolling funeral bell. For a moment, no one reacts, each individual crammed into the airless room privately digesting the verdict. Then, somewhere in the public gallery, a deep, full-bodied yell rings out. It sounds a bit like yeeeeeaaAAHH! – but it’s less an actual, identifiable word than a raw, unfiltered expression of emotion. There’s triumph in there, but also deep, agonising pain, harboured silently throughout the long months of the trial. Another sound, no less incongruous, follows from the other end of the gallery: a strangled laugh – less because the situation is genuinely funny, perhaps, than because it’s the only means the person responsible possesses to release the tension bottled up inside them. As excitement spreads like an unstoppable wave, another voice rises above the wordless tumult.

‘Rot in hell, you murdering bitch!’

At once, the mood seems to crystallise, as if these words have given voice to what everyone else has been thinking but, until now, has not been bold enough to articulate. A roar of agreement goes up at the back, someone lets out a whoop more suited to a rock concert than a place of solemn procedure, and a dozen more voices join the fray. As the noise grows to a crescendo, the judge – an old-school, donnish figure straight out of legal drama central casting – awakens from his torpor and calls for silence. This is not the way things are done. Not in his courtroom.

Silence resumes – gradually rather than all at once. Those that have risen to their feet retake their seats, chastened. All eyes are on the woman in the dock, flanked by a broad, white-shirted guard on either side, as the judge directs her to stand.

The public, seated behind her, don’t see her face, though it’s doubtful there’s a single person in the country unable to recall its every detail with pinpoint accuracy. The strong, square jaw. The thick, perpetually unbrushed dark hair. The thin-lipped mouth, permanently set in a straight, unsmiling line. And, of course, the pale blue eyes that are her most distinctive feature and on which so many of the press photographs have focused, earning her the moniker that has become as well-known as her actual name.

Ice Queen.

The judge is speaking now, addressing her directly. His monologue will soon be a matter of record, reproduced in every newspaper and on every television and radio bulletin in the next twenty-four hours. He tells her that mere words are insufficient to convey the barbarity of her crime, but of course goes on to use a great many anyway to do just that. A shocking crime. An unbelievable crime. A crime committed not just against the three victims but against all who believe in kindness, decency and the rule of law.

And throughout it all, she doesn’t move. Doesn’t react in any way. Journalists stationed in the press section of the gallery will attest that her face remains expressionless throughout the address, even though none of them are in a position to actually see it, and no one who reads their words will seriously doubt the veracity of this claim. Everyone knows the Ice Queen is incapable of emotion.

And now the judge has finished speaking, and it’s all over. Firm hands seize her upper arms and she is bundled down the steps leading from the dock, just like the condemned women and men taken straight to the gallows in days of old. Not that they hang people anymore in this country, despite how fervently several media pundits and members of the general populace might wish an exception could be made in this case.

The moment she disappears from view, pandemonium erupts in the gallery as press and punters alike scramble towards the exit. Edinburgh’s High Court is located in the heart of the city – a stately edifice dating back to the seventeenth century, surrounded by the touristy trappings of the picturesque Old Town. Today, the cobblestoned road on the building’s north side has been cordoned off at either end, with a dozen uniformed officers deployed to police the sizeable crowd that’s been gathering, in anticipation of a verdict, since before first light.

A prison van idles, facing away from the building, its tailgate slightly overlapping the kerb. The driver, leaning out of his window, flexes and unflexes his hands on the wheel. The mid-morning air prickles with nervous anticipation. Every face in the crowd is turned towards the building, each pair of eyes fixed on the plain wooden door, its ‘FIRE EXIT – KEEP CLEAR’ sign fooling no one. They’re a diverse bunch, with no clearly defined profile. Young, old, female, male, rich, poor – every conceivable demographic has a witness present. Several of the women have brought their young children with them, as if hoping to prove a point. A fun day out for all the family.

Just then, a shout goes up. It’s not clear what has prompted it, but a second later, the door opens and the first of the two guards steps out. Behind him walks the Ice Queen, wrists manacled in front of her, the hand of the second guard clamped firmly around her bicep as he brings up the rear.

The crowd presses forward, held back by officers armed only with batons where riot gear would have been more appropriate. Roars erupt. Jeers. Boos. A variety of colourful threats and epithets. The mothers with children present are among the loudest and most graphic in their descriptions of what they’d like to do to her. The machine-gun fire of camera shutters rattles unceasingly. Journalists bellow over one another, microphones and voice recorders thrust forward, as if they expect the prisoner to stop and take questions. She doesn’t react, those brilliant blue eyes as blank and devoid of expression as a china doll’s.

Something’s wrong. The van door won’t open. The first guard rattles the handle uselessly. Turns to his partner for assistance, or perhaps advice. One hand still on the prisoner, he moves forward and tries the handle himself with the other. No such luck.

The crowd is getting louder. Angrier. They’ve smelled blood, their prey almost within touching distance and barely protected. If just a few of them rushed forward en masse, they’d be unstoppable. The Ice Queen continues to stare straight ahead, seemingly unmoved by the precariousness of her plight.

Without warning, something strikes the first guard on the shoulder, hurled with considerable force from the rear of the crowd. He gives a grunt and looks down as a plastic water bottle rolls away from him over the cobblestones, a trickle of yellowish fluid spilling from its open end.

‘It’s piss,’ he says in disgust, as more of the liquid drips from his shirtsleeve and the hair at the back of his head.

A moment later, another projectile is hurled, and then another. A rock, a half-eaten banana, a traffic cone – the floodgates open as people rush to pick up whatever is to hand. One particularly zealous individual even removes and throws a platform shoe, which glances off the side of the van, leaving a dent in the bodywork.

‘Fucksake,’ the guard hisses as he continues to cling to the prisoner. ‘They’re gonnae lynch us.’

His partner redoubles his assault on the door, twisting the handle this way and that, hoping to find the sweet spot that will do the trick. The crowd surges forward on both sides, those at the front now actively grappling with the officers holding them at bay.

And then, as if by a miracle, the door swings open, and the two guards scramble inside, dragging the prisoner – who gives every impression of having been content to remain standing there to be torn limb from limb – behind them. The door slams shut, the engine revs, and the van takes off, the driver performing a ninety-degree turn in the narrow street that would put a professional stock car racer to shame. The police and the crowd part just in time as it roars up St Giles’ Street towards Lawnmarket, serenaded on its way by a fresh barrage of missiles and a few well-placed thumps from nearby fists.

Inside, the two guards sit facing each other on opposite benches, sweating and catching their breath as the danger recedes in the rearview mirror. Their eyes meet. Both laugh nervously. As his breathing settles, the one responsible for the prisoner turns to his charge, sitting impassively next to him on the bench.

‘Hope ye enjoyed that, darlin’.’ His voice drips with undisguised glee. ‘Wee taste of what the rest of yer life’s gonnae look like.’

If the Ice Queen has heard him, she gives no indication. She continues to gaze straight ahead, those pale blue eyes unblinking, unseeing, unperturbed, as if all this is but a passing inconvenience to her.

1

Tuesday 5 March 2019

It didn’t look much like a prison from the outside – but then, Anna supposed, they never did these days. With its glass-fronted façade, reflecting the cloud-stippled mid-afternoon sky, it could just as easily have been the entrance to a shopping centre or an airport terminal. In front of the building – which the ‘About’ section on the Scottish Prison Service website disarmingly referred to as the Visitors’ Centre – a large, rectangular granite slab occupied pride of place in the middle of the paved concourse, the words ‘WELCOME TO HMP BROADWOOD’ embossed on it in gold.

Broadwood, better known as the new women’s super-prison – built, at considerable expense, on the banks of Broadwood Loch in Cumbernauld; now home to almost all of the three hundred or so women in Scotland currently serving custodial sentences.

Anna stepped through the revolving door – an architectural choice which seemed almost postmodern in its self-awareness – and into an eerily silent foyer sporting carpet-tiled flooring and pastel-hued walls stencilled with an array of positive affirmations. ‘Sometimes the smallest step in the right direction ends up being the biggest step of your life.’ The waiting area was equipped with multicoloured polyester chairs and a children’s soft play area which, with its safety netting walls, bore more than a passing resemblance to a miniature prison for tots. Which, given the often intergenerational nature of offending, seemed appropriate, in a perverse sort of way. Might as well get ’em used to it while they were young.

She approached the desk, manned by a girl in her twenties with blonde hair in a severe ponytail and lips so glossy they looked like they’d been lacquered. She fixed Anna with a gleaming, toothy smile.

‘Welcome to HMP Broadwood. How may I help?’

Anna slid her Glasgow University ID across the surface. ‘Professor Anna Scavolini, here to interview Martina Macdonald.’

It had started life as an idea for a journal article, or perhaps an extended essay: an account of women’s experiences of the prison system, told in their own words. A chance to put the women themselves front and centre of the debate – a genuine collection of human stories as opposed to a dry academic treatise on policy which regarded them as objects on whom to ‘do research’. But the project had grown legs, refusing to let itself be contained within the scope of a single article, and eventually one of Anna’s colleagues – no doubt fed up hearing her lamenting this conundrum every day – had said to her, ‘This sounds more like a book.’ They’d put her in touch with an editor at a small, Glasgow-based academic press, who became duly excited by her pitch and commissioned her on the spot. Then, in short order, Anna was negotiating time off work to allow her to focus on researching and writing the book, freed from the obligations of teaching and running the university’s Criminology undergraduate programme.

And now, here she was, three months into the project, stepping into the belly of the beast for the first time. She’d been inside prisons of various stripes before and had visited the now decommissioned women’s facility at Cornton Vale half a dozen times over the years. But this felt different. All the women she’d spoken to so far for the book had been ex-prisoners – older women whose experiences of incarceration were rooted firmly in the past tense. Martina was the first woman currently serving a sentence who’d agreed to talk to her; the first who wasn’t looking back on her experience in the rearview mirror. And, of course, there were Anna’s own views on Broadwood and the circumstances surrounding its creation. Views which she’d already expressed forthrightly through a range of different forums – for what little good it had ultimately done.

But there was nothing she could do about any of that now. She just had to compartmentalise and focus on the task at hand. Go in, get what you need and get out – and don’t pick fights with the people that are just here to do their jobs. And so she dutifully submitted to the biometric fingerprint reader and to being photographed and stepping through the body scanner. Satchel and phone in the plastic tray, jewellery and belt off, legs splayed and arms outstretched while a heavyset male officer patted her down… Really, it was no different to going on your holidays. Lanyard issued, bearing her mugshot and ‘VISITOR’ in bold red; belongings stowed in one of the thirty or so metal lockers, barring the stationery and voice recorder she’d received special dispensation to take in with her – not to mention the all-important participant information sheet and consent form, to be completed by the interviewee as confirmation that she agreed to her experiences and reflections being quoted in the published text.

And then she was through security and being led by the guard down a narrow corridor, at the end of which stood a tall, grey-suited woman of around forty-five, with a peroxide blonde perm and the sort of straight-backed, upright posture that suggested an equestrian lifestyle – or a stint in traction.

‘Professor Scavolini.’ She greeted Anna with an overripe smile and extended a perfectly manicured hand. ‘So pleased to have you here with us today. I’m Ruth Laxton, governor of HMP Broadwood.’

She made it sound as if Anna was the one doing her a favour by being here rather than the other way round. It hadn’t been easy getting the go-ahead for today’s interview, her reputation as a critic of penal orthodoxy having doubtlessly preceded her. And then there were the safeguarding issues, which, Ruth had stressed, were her utmost concern. ‘Many of our ladies are extremely vulnerable,’ she’d said in her response to Anna’s initial email, as if she anticipated this being news to her. ‘I would require a cast iron guarantee that they will not be exploited or taken advantage of in any way.’

In the end, only one ‘resident’ – that was how Broadwood referred to those currently confined within its walls – had agreed to speak to Anna. Twenty-three-year-old Martina Macdonald was, from the little Anna already knew about her, an all too typical example of the trajectory of women within the prison system. In and out of a succession of care homes and young offenders’ institutes from an early age, she was currently fourteen months into a three-year stretch for assault and robbery, committed to feed a heroin habit she’d picked up during one of her previous stints behind bars. There was a young child in the picture somewhere as well, which, odds were, was currently at the beginning of the same ‘care to young offenders’ institute to prison’ trajectory as its mother.

‘I thought,’ said Ruth, as Anna fell into step with her, ‘you’d prefer to conduct your business in one of our private legal visitation rooms rather than the general family room. It’s slightly more of a trek, I’m afraid, but it’ll give you a chance to see the facilities we offer.’

They headed down another corridor and through two sets of security doors, which Ruth unlocked using a key card, before emerging into an open-air courtyard. A wide, well-tended lawn spread out before them, bisected by a footpath which led to the centre of the courtyard before splitting off into three different directions, each leading to a three-storey, Y-shaped brick building. It was a scene that wouldn’t have looked out of place on a modern university campus. Only the vertical bars in front of the windows hinted at the buildings’ true function.

‘As you can see, Broadwood has three houses,’ Ruth said; ‘Barbour, Inglis and Pankhurst. Each corresponds to one of three supervision levels – low, medium and high. At any given time, we can expect to have upwards of four hundred ladies staying with us – approximately seventy-five percent serving custodial sentences and the remaining twenty-five on remand. The number of women in custody in Scotland has almost doubled in the last decade, and the new facility has a fifty percent greater capacity than Cornton Vale.’

Anna, hurrying to keep up with the woman’s brisk stride, said nothing, though she couldn’t help noting Ruth’s apparent pride in these statistics, and that, despite the warm words from politicians of every conceivable hue about seeking to reduce custodial sentences, the place had clearly been built in anticipation of a growth in demand.

Off to the left, a couple of young women in dungarees and T-shirts were working in a flowerbed, armed with rakes. As Anna and Ruth drew nearer, they stopped what they were doing and stood, watching.

‘Haw, Mrs L!’ the taller of the two shouted, cupping her hands to her mouth. ‘Is that yer missus? Been holdin’ out on us, so ye have.’

The pair hooted with laughter.

Ruth halted and stood facing them, hands on hips. ‘If you’ve finished your chores for the day, girls, you are more than welcome to return to your rooms.’

The laughter died on the two women’s lips. They quickly snatched up their rakes and began to till the soil with abandon, if not with any sense of purpose. Ruth watched them for a few seconds longer, then, seemingly satisfied, gave a curt nod and continued on her way.

‘Several of our ladies come to us with behavioural problems,’ she explained, as Anna once more hurried to keep up. ‘They’ve not all had the best start in life. But we do our best to channel their energy into more productive pastimes. We’re firmly of the opinion that few things are more conducive to a state of equilibrium than an honest day’s work.’

They reached the entrance to the middle building – Pankhurst, according to the plaque above the door – and headed inside.

‘Of course,’ Ruth went on, as they made their way up a flight of stairs, ‘it’s not just endless grafting for no reward. Broadwood is equipped with multiple recreational facilities – separate football and netball pitches, a fully stocked library and lifelong learning suite, a state-of-the-art media centre… and all our guest-rooms are equipped with en suite facilities.’

‘Lucky them,’ said Anna, as they alighted on the first-floor landing.

‘Needless to say, we also offer a round-the-clock counselling service and have a dedicated detoxification unit for those suffering from alcohol or drug dependencies. The mental wellbeing of our residents is our utmost priority.’

As they continued down yet another pastel-walled corridor, a girl in a T-shirt and jogging bottoms came hurrying towards them. Even from a distance, Anna could tell she was in a highly agitated state.

‘Mrs Laxton, Mrs Laxton!’ she practically bellowed, coming to a halt facing them. ‘I need tae talk tae ye!’

‘Indoor voice, please, Chantelle,’ said Ruth. ‘We’ve spoken about this, remember?’

‘Sorry, Mrs Laxton.’ Chantelle took a deep breath and stood, cheeks puffed out, one leg jiggling impatiently. She couldn’t be much older than her late teens, though her manner struck Anna as that of someone considerably younger.

‘That’s better. Now, what’s the problem?’

‘It’s Kellyanne, Miss.’ Chantelle’s voice was a petulant whine. ‘She’s took my cigarettes and she willnae give them back.’

Ruth sighed and folded her arms behind her back. ‘And why did she take your cigarettes?’

Chantelle’s gaze dropped to floor, unable to meet Ruth’s eye. ‘Cos I shoved her Snoopy hoodie down the bog.’

‘I see. And you thought she’d just accept that lying down, did you?’

‘But Miss, she’s the one what started it, and—’

‘I’m not interested in who started it. All I’m interested in is that you get it sorted pronto.’ Ruth folded her arms and fixed Chantelle with an icy glare. ‘Now, are the two of you going to sit down together and resolve this like grown-ups, or am I going to have to revoke both your recreation room privileges?’

‘Yes, Miss.’ Chantelle’s voice was barely a mumble.

‘Hop to it, then.’

With a final, hasty ‘Yes, Miss’, Chantelle turned tail and set off at a sprint, heading back the way she’d come.

‘And no running in the corridor!’ Ruth called after her. She turned to Anna and shook her head. ‘A small taste of what we have to contend with. So many of these girls have no grasp of the ins and outs of civilised society – especially the ones who’ve grown up inside the system. They arrive here thinking they can resolve all their issues by engaging in tit-for-tat. It’s our job to make honest women out of them.’

‘Well, I wish you every success,’ said Anna, her mind immediately turning to the levels of recidivism among former inmates.

Ruth gave a strained smile. ‘And now, I’m sure you’re eager to get on. I’ll just find out if Martina’s ready for you…’

She retrieved her phone from the inner pocket of her jacket and, turning her back on Anna, dialled a number and put it to her ear. Taking the hint, Anna wandered in the opposite direction, admiring – if that was the right word for it – the tastelessly bland paintings of landscapes that adorned the walls. Behind her, she heard Ruth speaking in a low voice. Without meaning to, she found herself tuning into the words.

‘When was this? … I see. And is she…? … No, no, you did the right thing. … Yes, I’ll tell her. … What? … No, I don’t think that’s a good—’

She stopped abruptly. Anna, facing the other way, felt the governor’s eyes on her. A moment later, she heard Ruth’s footsteps retreating further up the corridor. When the conversation resumed, she could no longer make out any of the words – just a low murmur, barely audible over the hum of the radiator.

At length, the conversation concluded and she heard Ruth’s footsteps approaching. She turned, expression neutral but privately braced for bad news.

‘I’m afraid we have a slight hitch,’ said Ruth, folding and unfolding her hands as if she was trying to get grease off them. ‘Unfortunately, Martina Macdonald is no longer available to be interviewed.’

Wrong-footed, it took Anna a moment to respond. ‘Why? Has she withdrawn her consent?’

‘Not in so many words.’ Ruth had now taken to squeezing her hands together so tightly her fingertips were starting to go purple. ‘She’s become… indisposed.’

‘Indisposed?’

‘There’s been… an incident. She’s currently receiving treatment.’

Immediately, all manner of possible scenarios flashed through Anna’s mind – everything from slipping on a wet patch of floor to serious assault at the hands of another prisoner to an overdose, accidental or otherwise. Given the wall-to-wall press coverage of the recent spike in drug-related incidents among the prison population, coupled with what she knew about Martina’s own history, it was difficult not to regard the latter as the most likely.

‘What’s happened to her?’

Ruth winced. ‘Unfortunately, I’m bound by our confidentiality policy, but I can assure you, she’s being attended to and receiving excellent care.’ She gave an apologetic shrug. ‘Unfortunately, it looks very much like you’ve had a wasted journey.’

‘So it seems,’ Anna agreed.

In truth, she was less concerned about having come all this way for nothing than the wellbeing of a woman whose backstory positively screamed ‘vulnerable inmate’. Though, given how much of an uphill struggle it had been to secure Martina’s cooperation in the first place, she certainly didn’t relish the prospect of starting the whole rigmarole again from scratch.

‘I’d, ah, better show you out,’ Ruth said.

As she spoke, Anna felt an unexpected pang of something approaching sympathy for her. This woman might be the living, breathing embodiment of a system Anna wanted nothing more than to dismantle, but she was also in an unenviable position and doing her best for the inmates under her care, however much she and Anna might disagree about the current settlement.

‘Least I got a guided tour out of it,’ she offered, with a slight smile.

Ruth managed a small, fleeting smile of her own. She took a step towards Anna, then halted abruptly. ‘There is…’ she began, then stopped herself.

‘What?’

Ruth shook her head, dismissing Anna’s question with a wave. ‘No, no, forget it. It’s nothing.’

But if there was one thing Anna wasn’t going to stand for, it was having a carrot dangled in front of her and then immediately snatched away. She folded her arms, raising herself up on the balls of her feet to compensate for the height difference between them.

‘No, come on – what were you going to say?’

For a moment, Ruth looked like she was on the verge of digging in her heels. Then she seemed to change her mind, her posture becoming marginally less rigid.

‘I think, perhaps, this is a conversation that would be better suited to somewhere more private.’ She extended an arm. ‘My office?’

Ruth’s office was on the second floor at the front of the building, the large slider window behind her desk affording an all-encompassing view of the courtyard and the rest of the prison complex. Her desk, a spotlessly clean mahogany affair, was bare apart from a ridiculously tiny laptop, a plaque bearing her name and a grotesquely oversized framed photograph of herself shaking hands with a former First Minister. It was a toss-up as to which of them looked more pleased with this state of affairs.

Ruth shut the door and stood behind her desk, presumably under the impression that it made her appear more in control of the situation.

‘I debated whether to mention this,’ she said, ‘but I’ve concluded it would be dishonest of me not to say anything. Another prisoner has offered to talk to you in Martina’s place.’

Anna could sense the unspoken caveat. ‘Well, if she’s happy to speak to me, I certainly have no objections.’

Ruth sucked air through her teeth. ‘You might not think that once I tell you her identity.’

‘Why? Who is she?’

Ruth hesitated for a moment before responding.

‘The child-killer, Sandra Morton.’

2

Anna sucked in a heavy breath. ‘The Ice Queen,’ she murmured. As distasteful as the nickname had always seemed to her, it was so inextricably linked to the woman whose name Ruth had just invoked that it sprang to her lips almost unbidden.

From behind her desk, Ruth gave Anna a probing look. ‘What do you know about her?’

Anna cast her mind back. To call the case ‘infamous’ was doing a disservice to the word.

‘About the same as everyone else, I suppose,’ she said. ‘Convicted in 2002 of stabbing her husband and two infant sons to death while they slept. Pled not guilty, but eyewitnesses refuted her alibi. Multiple applications to the Appeal Court and to the Criminal Cases Review Commission, all unsuccessful. Received the longest sentence handed down to any woman in Scottish legal history.’

‘Forty-six years. Even if she only serves the minimum tariff, she’ll be eighty-one by the time she gets out.’

The overwhelming majority of women at Broadwood were serving terms of less than twelve months. Even among those convicted of the most severe crimes, minimum sentences were typically set at under twenty years. The length of the tariff had been controversial at the time, Anna remembered – though many had thought it too lenient.

‘And why has she decided to talk to me?’ This was, she belatedly realised, the most pertinent question.

Ruth hesitated – already, Anna could tell, regretting having said anything. ‘She takes these fancies now and then. Hers is not the sort of mind that’s suited to being locked up for twenty-three hours a day with no stimulation – which, as our highest security resident, is unfortunately her lot in life. For what I hope are obvious reasons, we keep her isolated from the rest of the population.’

She gestured to one of two cantilever chairs facing the desk, inviting Anna to take a seat. Anna did as she was bidden, waiting for Ruth to settle in the Chesterfield behind her desk.

‘As you can imagine,’ the governor went on, ‘with someone of Sandra Morton’s profile, all manner of journalists and psychiatrists are desperate to interview her, even after all the books and documentaries and podcasts. And, from time to time, Sandra obliges them with an audience. There’s no shortage of experts who think they’re the one who’s going to crack her – to figure out what made her do what she did. Sometimes, she’ll indulge them, feeding them a pack of lies about her childhood that can be disproved with even a cursory amount of research. Other times, she’ll agree to speak to someone, only to change her mind at the eleventh hour – often after they’ve been waiting in the interview room for hours. A couple of years ago, she agreed to talk to a world-renowned FBI profiler from Quantico. He flew over specially, went through the whole rigmarole of getting the paperwork in order. Then, as soon as she was seated in front of him, she took one look at him, said “I don’t like his tie”, and asked to be taken back to her cell.’

Despite herself, Anna couldn’t help but smile at the mental image of some self-important pseudoscientist having his balloon burst so spectacularly. Seeing Ruth’s stony expression, she hastily rearranged her face and cleared her throat.

‘And, in your opinion, is that what she has planned for me?’

Ruth considered the question. ‘In your case, I’d say it’s unlikely. You’re already here, so there’s a limit to how much of your time she can waste. If she does have an ulterior motive, it’s likely to be something rather more elaborate than ensuring you’re caught in the evening rush hour.’

‘You don’t think I should talk to her.’ It was a statement of fact rather than a question.

Ruth looked pensive. ‘I think,’ she said, choosing her words carefully, ‘that it would be better for the whole world if Sandra Morton simply faded into irrelevance instead of having her story dredged up again every six months in yet another lurid retrospective. I think engaging with her at all is giving her more attention than she deserves.’

Privately, Anna couldn’t help but concur. How often had she herself lamented the media’s grim focus on ‘celebrity’ killers, endlessly raking over the salacious details of their crimes, forcing their victims’ relatives to relive their trauma again and again, all while feeding the public’s prurient obsession with the worst excesses of human depravity? She was about to stress that that was the last thing she intended to do – that any interest she might have in Sandra Morton pertained purely to her experience of incarceration – when Ruth spoke again, her tone more conciliatory.

‘Having said that, if you’re looking for an up close and personal account of the prison experience, and assuming she does actually plan to cooperate, I doubt you’ll find anyone with a more comprehensive knowledge of the system. I don’t imagine there’s anything she hasn’t seen at least once.’ She gave a small, fatalistic shrug. ‘At the end of the day, it’s your decision.’

Anna thought about it. If she left now, she’d probably make it back to Glasgow in time to pick her son up from playgroup herself and have nothing worse to show for it than a wasted afternoon. On the other hand, and despite her deeply held misgivings about the morbid fascination that invariably surrounded cases like Sandra Morton’s, she had to acknowledge that at least a small part of her had more than a passing curiosity about this woman whose actions had generated so much public opprobrium; whose crime had become such a cornerstone of the zeitgeist that she felt she knew it inside out despite never having actively sought out information on it. She knew, if she passed up this opportunity, she’d be kicking herself for a long time to come. Plus, on a more straightforwardly human level, she recognised that Ruth, despite clearly having profound reservations, was trying to make amends for the wasted journey.

‘I’ll do it,’ she said, getting to her feet.

Ruth rose from her chair too, disapproval still writ large on her features. ‘In that case, I’ll make the necessary arrangements. Just be forewarned: you can never be certain which version of Sandra you’re going to get. She can be completely affable, or she can be so indifferent towards you that she won’t even acknowledge your presence. It all depends what sort of mood she’s in. Assuming she doesn’t blank you completely or tell you to leave as soon as she lays eyes on you, I’d strongly advise against sharing any personal information about yourself.’

Anna couldn’t help but give a wry smile. ‘Yes, I saw that film as well.’

Ruth fixed Anna with a stony look. ‘It’s no laughing matter. Sandra Morton might not be capable of persuading you to peel off your face or swallow your own tongue, but don’t for a minute underestimate how manipulative she is. If she senses a weakness in you that she can twist to her advantage, believe me, she’ll use it – if only for the satisfaction of taking you down a peg or two.’

The décor of the visitation room was of a piece with the rest of the prison, but, for the first time, Anna observed cracks in the façade. The table was bolted to the floor, there was a brown stain on the pale blue wall where someone had hurled what she hoped was coffee, and several of the available surfaces had been augmented with graffiti – including the declaration, gouged into the tabletop, that ‘Stacey B is gagging for muff’.

Seated facing the door, Anna busied herself with making sure her audio device was properly set up, laying out the consent form, information sheet and pen, then checking the audio device again. She clocked the slight tremble in her right hand and squeezed it with her left until it settled.

Stop it. She’s just a prisoner like any other. Don’t make her into something she’s not.

She heard footsteps approaching in the corridor – several heavy pairs of boots, all moving at the same steady pace. She sat up a little straighter. Swallowed. Folded her hands on the tabletop, ready for business.

A moment later, the door swung open. A middle-aged male prison officer entered first, like a scout sent ahead to scope out the terrain. Others loomed in the doorway behind him – at least four, a mixture of male and female. Standing bang in the middle of the cluster – the odd one out with her grey sweater and bright red tabard amid a sea of white shirts and black ties – was the woman the press had dubbed the Ice Queen.

A part of Anna had expected Sandra Morton to be wearing an orange jumpsuit and clapped in leg irons, her movements restricted to the bare minimum. Even for someone as well versed in the particulars of Scotland’s prison system as her, the influence of imagery from American maximum-security penitentiaries was hard to shake. Instead, the woman who now stepped into the room was completely unrestrained, though one of the officers forming the rear-guard – a young man with a bum-fluff goatee – followed closely behind her, one hand hovering in the general vicinity of her shoulder without touching her, as if he feared to make physical contact. The woman glanced briefly at the empty seat in front of her, as if checking it for cleanliness, before plonking herself down. She leaned back, folded her arms and looked Anna up and down.

‘You’re shorter than I expected,’ she said.

As far as opening gambits went, it was certainly to the point.

‘Has anyone offered you any refreshments?’

‘Oh no.’ Anna’s response was instinctual, like a child conditioned never to accept sweets from strangers. ‘I—’

‘I’ll have a black tea,’ Sandra said, not addressing this demand to anyone in particular.

The officer who’d entered the room first, and who was clearly in charge, nodded to his colleague with the bum-fluff. ‘See to that, Gary, will you?’ He turned to the gaggle of officers milling in the corridor. ‘The rest of you, clear off. This isn’t a spectator sport. Plenty more work to be done.’

The officers dispersed, including Gary, shutting the door behind him on his way out. As the one who’d dished out the orders assumed an arms-folded position against the far wall, Sandra shot Anna a conspiratorial look.

‘My entourage,’ she explained. ‘For my own safety. Curiously enough, plenty of folk in here would happily take a pop at me if the opportunity arose. Wouldn’t be the first time.’

She pointed briefly to the side of her neck, where the skin looked puckered and papery – an old burn scar. It was known in the trade as a ‘jugging’: a form of so-called rough justice popular among the prison population involving a mixture of boiling water and sugar. Anna hastily averted her eyes.

‘Ms Morton,’ she began, fumbling with her paperwork to distract herself from the gruesome mental image, ‘can I start by thanking you for agreeing to this—’

‘Oh, Sandra – please,’ said the other woman, her tone verging on camp. ‘We keep things informal around here – first name terms only. One of the sainted Mrs Laxton’s little initiatives – though you’ll note she herself is exempted from this policy. First among equals, you see.’

She had a relatively neutral accent, not all that dissimilar to Anna’s own: standard, educated Scottish, with few, if any, specific regional identifiers.

‘Sandra, then. Before we start, I’d like to—’

‘Your professorship’s a recent appointment, isn’t it?’ Sandra cut in again, her tone measured but just loud enough to knock Anna off her stride.

Anna pressed her lips together and took a deep breath. She’d encountered this sort of thing before: the carefully timed interruptions, each one perfectly calibrated to throw her off her stride. In her experience, however, it was usually men of a certain age who indulged in this sort of behaviour. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d been subjected to these disruption tactics by another woman.

She put down her paper and lifted her head, forcing herself to look Sandra square in those pale blue eyes. Like ice crystals, she thought – and just as impenetrable.

‘What makes you say that?’ She kept her tone measured and indifferent.

Sandra smiled enigmatically. ‘You tell me.’

‘I asked first.’ Anna’s expression didn’t waver.

‘Well,’ – Sandra gave a slight eye-roll, as if she was spelling out something exceedingly obvious – ‘given your relative youth, unless you happened to be a child prodigy, there can’t be too many alternative explanations.’

Put like that, Anna couldn’t help but feel more than a little foolish. She pressed on, speaking louder this time in an effort to forestall any further interruptions. ‘Before we start, I’d like to ask whether you’re comfortable with me recording our conversation.’

Sandra spread her palms, Jesus-style. ‘By all means. When I received my sentence, I waved goodbye to all the rights we human beings normally take for granted, including the right to privacy.’

Anna pushed the information sheet towards her. ‘If you could read this as well. It explains the purpose of the research, how your contributions will be used, your right to withdraw your consent and the steps that will be taken to anonymise the data.’

Sandra flashed an amused grin as she took the sheet. ‘Anonymisation might be a tad tricky in this case. I doubt there are many others in the system with a comparable résumé.’

Anna pushed the consent form, and her pen, across the table. ‘And I’ll need you to sign this.’

Putting the information sheet to one side, Sandra picked up the form and began to read it. It soon became clear that, far from merely skimming it, she was intent on reading the whole thing from beginning to end, her eyes gliding slowly from left to right, pausing occasionally as she carefully considered – or pretended to consider – a particular clause before moving on.

The lull in conversation gave Anna an opportunity to properly observe her for the first time. She was a large woman – not in the sense that she was overweight or even particularly tall, but she seemed to fully fill the space she occupied. Anna had seen prisoners and ex-prisoners who, fearful of being attacked or having their food snatched from their plates, had become accustomed to sitting hunched over, shoulders tucked in, furtively guarding against wandering hands. Not so Sandra, who leant back in her seat, shoulders flung back, legs planted firmly apart, holding the page at arm’s length in a way that suggested long-sightedness coupled with a reluctance to admit to needing glasses. For a woman in her early fifties, and one who wore no makeup, her face was remarkably free of any age-related blemishes. Her hair, scraped into an unfussy bun, bore a handful of grey flecks but was otherwise as thick and dark as it had been in the pictures of her that had appeared in every newspaper and on every television screen for months on end almost two decades ago.

Seemingly satisfied, Sandra put down the form, picked up the pen and signed her name – a languid, unfussy scrawl – before sliding it back across the table.

Anna folded and pocketed the form, then cast around for her pen, only to realise Sandra still had it. She watched as the older woman toyed with it, turning it this way and that as if trying to make sense of how it worked. Anna squirmed internally. People stealing her stationery was a personal bugbear at the best of times, and now her mind couldn’t help but leap to all manner of extreme scenarios – everything from Sandra using it to pick the lock on her cell door to her leaping across this very table and stabbing Anna with it before her seemingly catatonic minder even had a chance to register what was going on.

‘Can I have that back, please?’ Anna gestured to the pen. ‘Um… so I can take notes.’

Sandra frowned. ‘Why would you need to take notes if you’re recording the conversation?’

As Anna racked her brains for a believable excuse, a knowing smile crept over Sandra’s lips. With a look that made it abundantly clear she knew only too well what Anna had been thinking, she reached across the table, holding out the pen.

‘Thank you,’ said Anna, taking it and laying it on top of her open notebook, positioning them both as far from Sandra as she could without making it obvious. ‘Now, if you’re happy to make a start—’

At that moment, there was a knock on the door.

‘Ah, good.’ Sandra glanced over her shoulder. ‘Here are the caterers.’

‘Come in,’ the guard called gruffly.

The door opened and Gary entered, carrying a tray loaded with various items: a cup, with accompanying saucer and spoon, an urn, a pack of Tetley teabags and even a couple of digestive biscuits. As he set it down in front of Sandra, she nodded approvingly.

‘Oh, Gary, you’ve outdone yourself this time.’

A brief smile flickered on Gary’s lips, followed by a frown, as he tried to work out whether he was being mocked or genuinely complimented. At a nod from his older colleague, he withdrew from the room, shutting the door behind him.

Sandra poured water from the urn into her cup. As Anna watched, on the verge of incredulity, she selected a teabag, tied the string round her pinkie and proceeded to dip it in the water – an incongruously dainty gesture for such a brawny woman.

Anna shifted in her seat, anxious to get on but feeling somehow reluctant to interrupt this curious ritual. She was just on the verge of saying something when Sandra glanced up, gave her a quizzical look and nodded towards the voice recorder.

‘Aren’t you going to switch that on?’

Feeling decidedly foolish yet again, Anna reached for the device and switched it on, hands fumbling over the buttons. She placed it in the middle of the table, sat up straight and cleared her throat for what felt like the umpteenth time since she’d first set foot in this place.

‘Anna Scavolini interviewing Sandra Morton at HMP Broadwood at 2.47 p.m. on Tuesday 5 March 2019.’

To be continued...

Buy Now

Women Who Kill, the gripping fourth instalment in the Anna Scavolini mysteries series, is now available in ebook and paperback.

Kindle Paperback Signed PBK