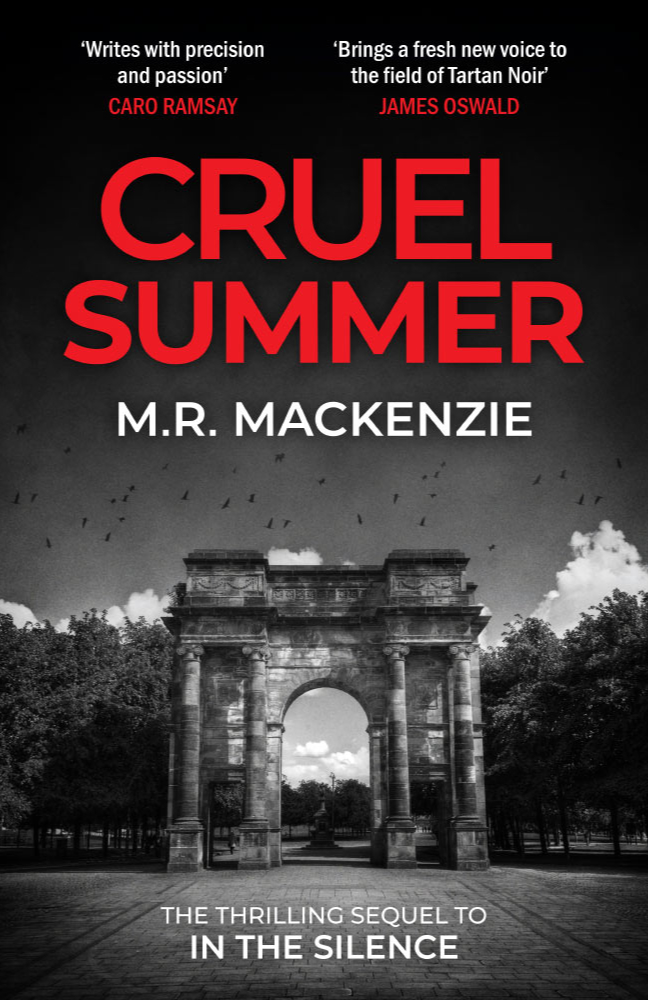

An extract from Cruel Summer

Zoe Callahan is having the summer from hell, and it’s about to get a whole lot worse. A rape trial, a corrupt politician and a ruthless crime syndicate collide in an explosive thriller set against the backdrop of a sweltering heatwave.

Cruel Summer, sequel to the McIlvanney Prize-nominated In the Silence and the second instalment in the Kelvingrove Park Trilogy, is now available in eBook and paperback.

Read on for a sneak peek at the prologue and an excerpt from Chapter 3.

Prologue

Hogmanay, 2012

The summons came, as always, via a call to Ryland’s private line. The appointed hour was 8.30 p.m., the place: Lombardini’s on the top floor of Princes Square shopping centre. A reservation had been made in the usual name. On his arrival, the waitress informed him they’d been expecting him and showed him to a table for two.

Alone at the small balcony table, Ryland gazed out at his surroundings. The square had first opened to the public in the late eighties, coinciding with Glasgow’s great renewal as a City of Culture – a gaudy, glitzy affair, all designer shops and glass elevators, designed to inject some cosmopolitan glamour into the lives of the commoners. Multiple conversations mingled with snatches of half-recognised lyrics as neighbouring restaurants pumped out competing songs. He could see why the venue had been chosen. Anyone listening in would be hard pressed to hear anything over the din. Not that he was unduly worried about being eavesdropped on tonight. His wasn’t a face you tended to see splashed across the front pages of the tabloids. Being a backbench MSP for the third-largest party – or third-smallest, depending on how you wanted to look at it – did have its advantages when one wished for anonymity.

His dining companion arrived over twenty minutes late and without even the grace to muster an apology. Huffing and puffing, he collapsed into the seat opposite, summoned a passing waiter with a florid wave and ordered himself a dry martini. As the waiter departed, he folded his pudgy hands across his round little belly and gave what was presumably meant to be a smile – though, given his rather unfortunate features, it looked more like a leering grimace. He was a short, bug-eyed little man with the jowly cheeks, grossly protruding bottom lip and non-existent chin that seemed to afflict so much of the political establishment. He had a name, of course, but Ryland had privately christened him the Poison Dwarf.

‘So, laddie, how does life find one this fine evening?’

‘Can’t complain.’

Ryland was hoping they could skip the pleasantries and get straight to business. He could think of umpteen things he’d rather be doing on Hogmanay night than spending it in the company of the Party’s vice-chairman and go-to hatchet man.

‘Splendid, splendid. And the good lady wife? She fine and dandy? Been having rather a rum time this last year, by all accounts.’

‘Doing much better since she started seeing that new chap.’

‘New doc an improvement on the old one, hmm? Marvellous, just marvellous.’ The Poison Dwarf gave another of his unfortunate smiles, then turned to his menu. ‘What looks good?’

They continued in this vein for another quarter-hour – the bland, hollow inquiries as to the wellbeing of significant others, the trading of war stories about their respective Christmases. It wasn’t until starters and main courses had been ordered, and they’d nearly finished the first round of drinks, that the Dwarf finally deigned to move beyond the banalities.

‘You’ll have heard the rumblings about the Farmer,’ he said, nonchalantly picking a fleck of dandruff off the collar of his pinstriped three-piece.

The Farmer. Archibald Adam Croft, sixty-four-year-old leader of the Conservative Party in Scotland, so nicknamed not because he was one but because he represented the fiercely rural constituency of Selkirkshire North, coupled with his fondness for being photographed in rolling fields, decked out with flat cap, jodhpurs and hiking staff. The surname didn’t hurt either.

‘I’ve heard rumours,’ said Ryland cautiously.

‘Oh, they aren’t just rumours, dear boy. It’s all but official now. In the coming months, the dedicated but charisma-deprived leader of our little group in Holyrood will announce his retirement from the front line, ostensibly on health grounds. Not keeping too well these days, they say. Dicky ticker.’

‘That’s regrettable.’

‘Not for us it’s not.’ The Dwarf tapped the side of his nose. ‘Events, dear boy, events. Not to put too fine a point on it, but the Elders have been – shall we say ambivalent? – about the man’s performance for some time now. The phrase “shoogly peg” springs increasingly to mind. Oh, they were content enough to put up with him for a spell – let him settle in, give him a couple of elections to find his feet. Right sort of chap, y’see. Anyway’ – he paused, glancing left and right, as if concerned that the nearby creeping ivy might have sprouted ears – ‘of late, the Elders have begun asking questions. The party successfully turned around its fortunes down south a few years ago, which begs the question: why is its northern chapter still firmly perched on the remedial step, placing third or even fourth in election after election? Well?’

Ryland said nothing. He suspected an answer would be forthcoming irrespective of his input.

‘Image.’ The Dwarf stabbed the table surface with a stout index finger. ‘The prevailing wind is that a new approach is needed. Out with the tweedy landowners and in with… well, the sort of people that actually win elections. Some charismatic young go-getter who can inspire folk’s imaginations and persuade the average voter that we’re not just the party for octogenarians. And, if he can do a respectable job of not looking repulsed when someone thrusts a photogenic infant into his arms, so much the better.’

He was referring to a notorious incident during the last election campaign when an enterprising strategist had arranged for a local party member to hand her newborn to Croft, anticipating a photo op of the sort that won votes from young mothers. Far from taking the stunt in his stride, Croft had immediately become stricken with horror, the expression on his face suggesting he would have been more at ease if someone had handed him a bundle of steaming manure. Not to be outdone, the baby had promptly begun to howl, and both child and party leader had had to be separated from one another before things got any worse. The Conservatives had gone on to lose the local seat, which they’d previously held since the Parliament’s opening in 1999.

Ryland allowed himself a thin smile. ‘What you’re saying makes complete sense, but the difficulty is finding someone who fits the bill. Not to put too fine a point on it, but pickings aren’t exactly rich among the current crop.’

‘Oh, I can think of one or two names.’

‘Such as…?’

The Dwarf cocked his head slightly to one side and extended his oily smile.

Realisation dawned on Ryland. ‘You cannot be serious.’

The Dwarf spread his arms. ‘And why not? You can’t deny you tick all the requisite boxes. Don’t tell me you think you’re not up to it.’

‘It’s not that. It’s just…’ He paused to collect his thoughts, then took a measured breath and went on, ‘Well, for starters, I’m a list MSP, and a backbencher at that.’

‘Why, my dear fellow, so much the better. I doubt there’s a single figure on the frontbench not mired in corruption and sleaze. You’ll be a fresh face – no existing baggage attached. I’m telling you, laddie, it’s all grist to the mill.’

‘Aren’t we getting ahead of ourselves here? Who out of the current mob would back me? I’d need—’

‘One hundred nominations, yes.’ The Dwarf was growing impatient. ‘Hardly an insurmountable challenge. And the support of at least a handful of elected representatives, past or present. Again, that can be arranged.’ Another furtive glance in both directions of traffic, and another drop in volume, so that Ryland now found himself having to lean forward to make him out. ‘Our mutual friend,’ he said, ‘very much wants to see this happen. He intends to make it abundantly clear to the relevant people that your successful application is to be little more than a box-ticking exercise, and that your bid will have the full weight of the party machine behind it.’

The latest mouthful of G&T turned to oil in Ryland’s mouth. Our mutual friend. Should have guessed he was behind this.

‘It’s the bright young things who’ll secure our future, you know.’ The Dwarf was in full flow now, savouring the sound of his own voice. ‘Even the most dyed-in-the-wool of the old guard are coming round to accepting that. The face of the new, trendy, modern conservatism – more relatable, more in touch with the hoi polloi. Public school but not too public school. The Jockos will never elect an Old Etonian, that much we know. But a poor boy made good who’s retained just enough of the local patois to pass muster as one of their own? Therein lie the seeds of our eventual rebirth, dear boy.’

Seeing that his previous efforts had fallen entirely on deaf ears, Ryland played his last card. ‘Truth be told, Alice has been hankering for a move back down south for some time. Climate up here’s never agreed with her, you see. Too much damp. Bad for her allergies. And just between us, last time we rubbed shoulders, the PM was making favourable noises about a seat down there becoming available. And, well, that’s a gift horse one can’t exactly afford to look in the mouth.’

The Dwarf’s smile faded, all trace of bonhomie leaving his features. ‘Let’s be toe-curlingly honest for a moment, dear boy. This isn’t up for negotiation. Our mutual friend has made his feelings quite clear. Always remember, the Lord giveth, and the Lord taketh away.’

Ryland didn’t reply. His mouth tasted like ash, and his glass had chosen this most inopportune of moments to be bone-dry. The hubbub of conversation around him continued unabated. On the speaker system in a nearby café, Mariah Carey was butchering Auld Lang Syne. Like oil and water, some things just weren’t meant to go together.

The Dwarf continued to fix Ryland with his icy stare. ‘He put you where you are today, and he can and will see to it that everything you’ve acquired – the wealth, the status, that asinine column you write for the Spectator – goes up in smoke the moment you’re no longer useful.’ He paused to take a sip from his own, irritatingly full, glass. ‘As for holding out in the hope that there’s a better offer waiting in the wings – some safe seat in the Shires where the local bumpkins will elect a donkey provided it’s wearing a blue rosette – forget it. The grandees of the Home Counties would never have it. Public school but not too public school, remember? And the accent you’ve gone to such pains to mask?’ He tutted. ‘No one’s buying it. But put in the man-hours, do as you’re “telt”, and we might just let you manage our wee Scotch region more or less as you see fit.’ He inclined his head to one side, smiling the smile of a man who knows he holds all the cards.

Not for the first time, Ryland reflected that those whom fate had deigned to make his political bedfellows were a truly remarkable bunch – the only people he’d ever met who were capable of both sneering and cringing at the same time. People who knew they were a breed apart, but who also knew their place in the hierarchy and relished their status in life’s natural pecking order.

‘You shit,’ he said. ‘You absolute shit.’

‘The Elders expect Croft to announce his intention to stand down in March. April at the latest. And by expect, I naturally mean insist. That means a spring campaign, making the most of the brighter days and longer nights, followed by the election in July or August. That gives us ample time to build your profile – get you in the right papers, shake hands with the right community leaders. You know how the charade goes.’

‘I do indeed,’ said Ryland, his tone devoid of any emotion.

The Dwarf smiled. ‘So pleased we understand one another. We’ll meet again early in the New Year. Discuss strategies, personnel, begin sowing the seeds of our future triumph, all that rot. Breathe not a word to anyone in the meantime. Not even your better half.’ He drained his glass. ‘I, ah, shan’t stay for dinner after all. A pleasant New Year when it comes. Give my regards to the good lady wife.’

He got up, threw on his coat with a flourish and strode out, giving Ryland a brisk pat on the shoulder as he passed.

Ryland was so deep in thought when the waiter brought his food that he barely noticed. He had much to ponder. They had him over a barrel; trussed up like the proverbial Christmas turkey. He was used to being treated like a piece on a board; to the feeling that others besides himself were in control of his life’s trajectory. And yet, even as he sat there, silently cursing the Poison Dwarf and the Elders and their mutual friend and the ground they all walked on, the words of a former leader of the party to which, for better or worse, his fate was intertwined, came to mind:

A pessimist sees the difficulty in every opportunity; an optimist sees the opportunity in every difficulty.

Stirring words, no doubt, but he’d always considered them just that – words on a page, to be trotted out as the climax to a rousing speech or as part of some generic appeal to the virtues of entrepreneurialism and self-sufficiency, in a pull up your socks and stop moaning about your lot in life sort of way. Now, though, he wondered if perhaps he should be taking them to heart himself. Though the situation he found himself in was neither of his making nor his choosing, it also presented him with an opportunity few men even dreamed of – provided he had the mettle to grab the bull by the horns.

Carpe diem and all that.